I have had a love of Julian Schnabel and his paintings since 1978, and through the years to 2026, just now, when I recently saw them at Mnuchin Gallery, in NYC.

I was introduced to Julian in a pivotal time, and at a momentous party for Larry Rivers, given by Nathan Joseph across from Joni Mitchell’s artist loft in Soho, maybe in 1977.

He was introduced as a figurative painter, myself identified as a figurative painter also, I wondered of the association. I was of the more traditional lineage. Paul Georges and Fairfield Porter leading to Alex Katz. Julian was more out of Philip Guston and his abstract roots. Guston was teaching at the Studio School where many of my friends were so there was a link. But Julian was also privy to the Whitney Program’s forward ideas of experimentation and a strong relation to the Art World’s culture of the time.

I was out in Long Island in the summers and Jackson Pollock permeated the atmosphere. My girlfriend worked for Helen Frankenthaler and many of my friends were abstract painters, though older like Poons, Christensen, and Zox.

When I say love above, it is in the connection of that moment to Julian’s in relating an image to that abstract surface. We didn’t know yet of the profound relation of an inner and outer reality, it’s collision and later relationship.

In those days every move was recorded in the Soho News, in Art in America, Art News and Art Forum. In Vogue, in the New York Times, in New York Magazine in the myriad voices registering each move. In Ross Bleckner, and David Salle’s, work I often felt I had just read the same article and had a similar response in my paintings.

We would go from the downtown bars to Julian’s opening at Mary Boone, amazed at Julians effort, The Doctors and the Patients, painted on broken crockery. Jabbing him on the arm— that he had really done it. Had made the outsized motion we all searched for.

Different formal moves were new and immediate registered, by us all. Salle and Schnabel were in the forefront and had a dialogue in between themselves even painting on each other’s paintings. I went home and made my own.

It was an exciting time and I was offered a job in CA, I had few options and there was a salary, a working studio and wonderful landscape space. I should have stayed in NY probably it was the most fertile time and was soon to dissipate in strategies of that Art World culture seemingly corrupting those exciting discoveries.

I was out painting 10’ paintings on the beach. I was making my own large gesture. It was a reaction to the repressive 70’s we all felt lucky to have emerged from.

I missed Julian’s big Leo Castelli show, but the media got the images out there and I knew them, and every other artist’s move by heart. By 1984 when I had my first one person show in SoHo things were well on there way.

Julian as the leader of this atmosphere was now isolated at his openings, surrounded by glamorous models, and Art World movers. We would wave a last good luck, and congratulations.

Somehow the importance of those exciting formal moves became rote. Everyone was incorporating the moves. It became about charisma and presentation. Ultimately money supplied the pathway. One could not express such a view as everyone was on this ‘hopeful’ path, looking for their big break.

In 1989 I guess I got mine but it was of an opposite way of thinking. Harold Bloom recognized what he thought as the authenticity of my work and applied the word Sublime to it. Not the charismatic Sublime, but the Sublime of authenticity and well probably those early gestures of Schnabel and also Kiefer equally powerful.

Harold in his essay, termed the now seeming lost gesture as, “ imposters, fashionable painters, and inchoate rhap-sodes.” Well my big break although I was centered in some of the best criticism of our time— I was effectively a goner.

Critics like David Shapiro, and his student Barry Schwabsky, and a small group at the time saw the value of Harold’s essay. It became the cover of Arts Magazine, and I had small retrospectives in Pennsylvania and California and Hawaii. But there was no money and the Art World machinery was nowhere to be seen. It went no further and the SoHo art world began to close up. So I was seen as Sincere and Earnest. The Irony and the Reality of this cultures’s ethos, as being essentially weightless, in the face of a dwindling criticism, lead us to all be out there on our own.

Many like Julian had so much still in place it would last and become what was left of a missed possibility, the possibility that Art could have the place it did in early Modernism and the authentic Expressionist gesture of Abstract artists like Pollock and Newman, Rothko and deKooning.

Serra, Johns, and Marden set an examples of this authentic reality but few had the tenacity to hold on to their difficult realities. Julian stayed in the near background for all these years because of the physicality he discovered to represent what profundities he did unearth in those early days.

In returning to California and the freedom I enjoyed there not having the comfort of support, I explored, looking for new ideas, watching for any hint of a new energy.

I found it in the Sublime of the natural world. But even that Natural Sublime seemed too uncomfortably edgy for our now plush world ignoring any of the real Horrors, the Horrors, of a dissappearing individual freedom and an environment in which to practice it.

I saw Schnabel’s 2026, Mnuchin show. Though I’d seen the works now many times at different venues which showed then to much better effect, as the Peter Brandt show. The works have a depth at times that reach deep into our humanity. He is a great artist. Julian though is maddening in how he is so involved in the fame thing as Warhol, he is enthralled by it.

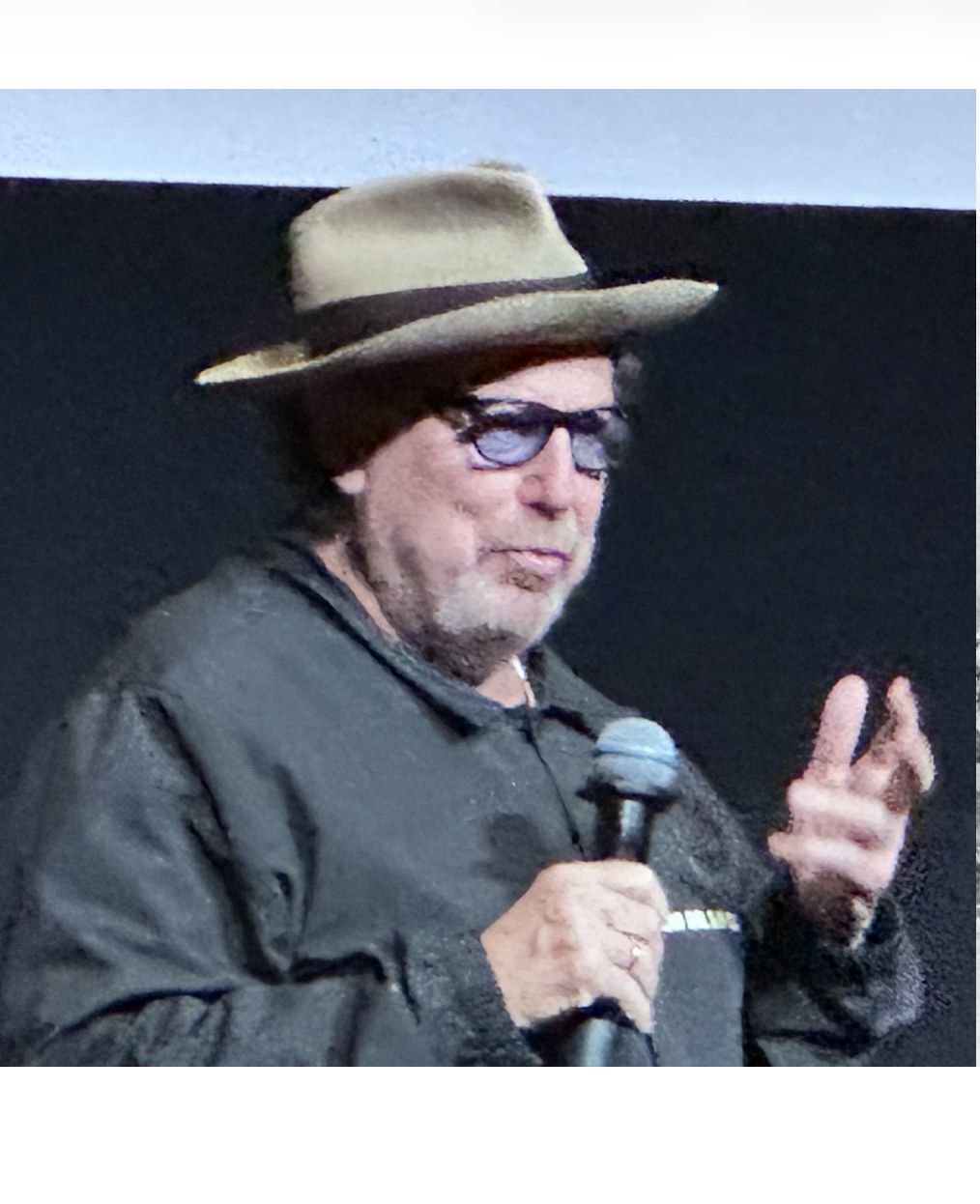

Getting now to the movie, he went on for five minutes about Johnny Depp and what a great painter he was regardless of actually how little he agreed with his methods.

His movie In the Hand of Dante, plays the game. It is peppered with the violence although it toughens the film’s ideas at places— possibly, it is the violence we have created ourselves to aggrandize ourselves in our plush anesthetized world.

The Dante which the movie purports to be about is seemingly pretentious. I would have loved to have reflected for any moment on any of the wonderful text collaged into the finally Hollywood medium however deep its pretensions. I can only reflect upon Trauffalt’s wondering if the medium of film would ever last or be worthwhile in relation to great Art.

But Julian is capable of bringing to the fore wonderful Ideas like the ‘sigh’, of art, when the artist becomes his poem.

Then, falls pretty flat when he blows a single hole in the head of a victim saying “this is where your soul was.”

None of this though would matter except that Julian was using Dante, Dante to establish the gravity of his thoughts or ones he found in the screen play or text he used for the movie.

Maybe the gunshots ringing out like Reservoir Dogs or Bad Lieutenant are the broken plates he ‘draws’ upon to register our broken time. I looked for a healing device, a word of strength as Dante certainly can deliver. Our art has done little to mend our horrendous moment.

Julians paintings did this though. Maybe, as Julian received a luke warm reception there at the Santa Barbara Film Festival, Julian in a look of desperation asked, “Is there a reason to do anything?” I looked in writing this for an answer.